The peasantry on the eve of the reform of Peter Stolypin

The peasantry in the late XIX-XX centuries in the Russian Empire, despite the abolition of serfdom, was still in an unenviable position. At the same time, in the provinces of European and central parts of Russia, the rural population from 1860 to 1900 increased from 50 million to 86 million, but at the same time, the land allotments that they could own decreased by the beginning of the twentieth century from 4.8 dessiatine per male population to an average of 2.8 acres. Nearly 11 million peasant households had as much land as 30,000 landowners. The productivity of peasant labor in that era also left much to be desired. All because of the very organization of work of such farms. Not only could the peasants cultivate the land only partially, literally narrow strips of fields located in different places, they also could not dispose of them at their discretion, that is, it did not belong to them on the basis of property, but the Community was responsible for its use. It determined how much and which family to give land to. While, where the peasants were masters of their land and the productivity was higher and there was no hunger. Such state policy created the most favorable conditions for all kinds of revolutionary parties. Their propaganda, in turn, directed mainly against the tsarist government, was conducted in the most active way. What did they promise the poor peasants? They promised what the state could not, or perhaps did not want to give — to distribute the land of the landowners. The inability to voluntarily leave the Community and the lack of private ownership of land were perhaps the key reasons that the peasants could not firmly stand on their own feet and develop their business. It was necessary to give them freedom of action, to untie their hands. Thereby creating a powerful layer of strong peasant farms, which in the future would become the basis for the successful development of the country. Here is what Peter Stolypin, the author of future agrarian transformations, stated at a meeting of the State Duma: “At present, the state is ill,” he said, “the most sick, the weakest part that is growing more weak is the peasantry. It needs help. A simple, completely automatic way is proposed: to take and divide all 130,000 existing estates. Is it state? Does this not remind you of the story of Trishkin Kaftan? - robbing one's belly to cover one's back? Gentlemen, it is impossible to strengthen a sick body by feeding it pieces of meat cut from it; it’s necessary to give an impetus to the body, to create a rush of nutritious juices to the sore spot, and then the body will overpower the disease”.

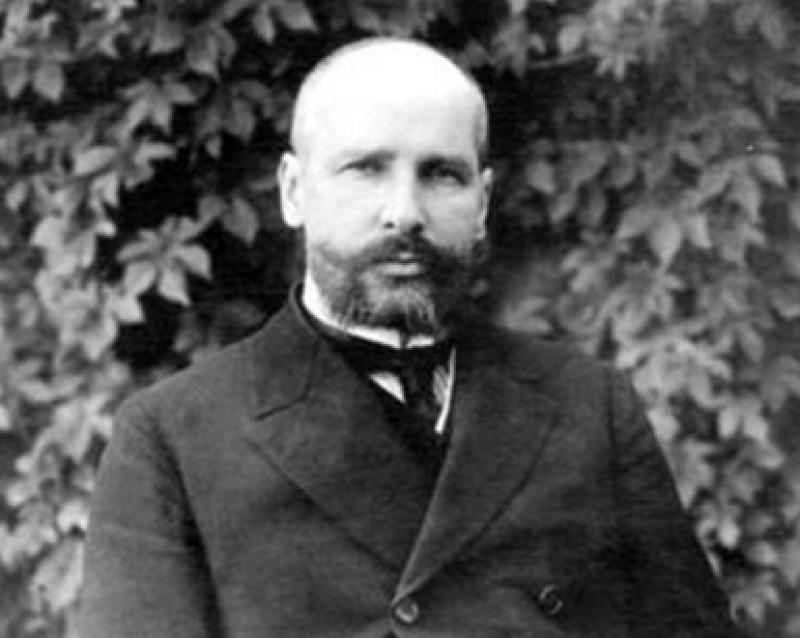

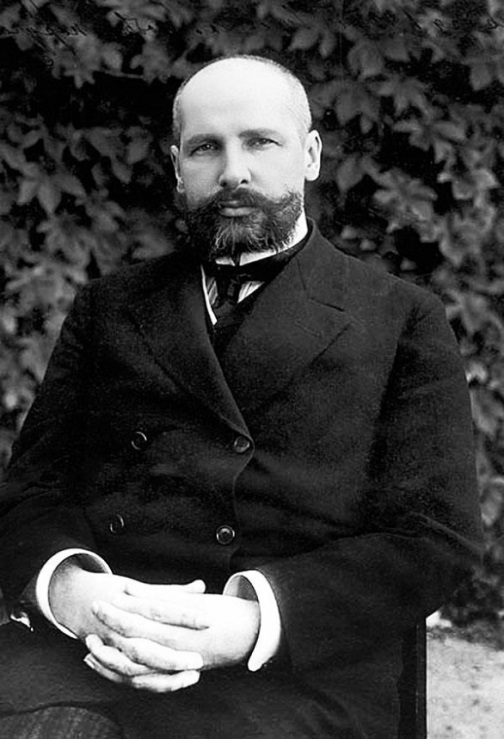

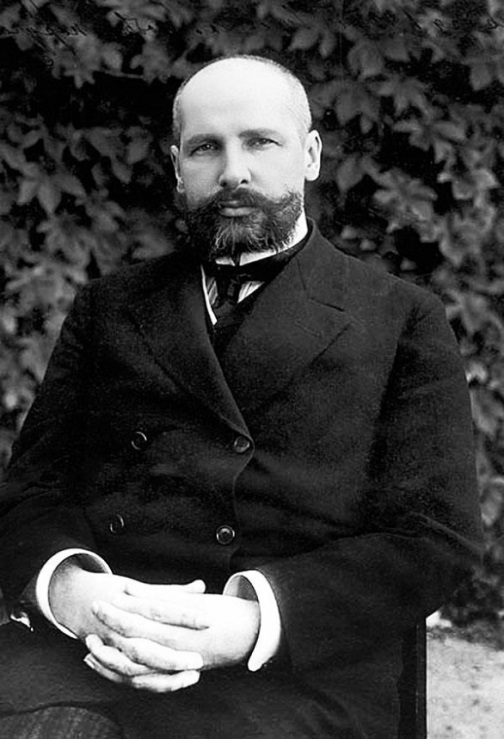

Photo by oko-planet.su

Then the Russo-Japanese War broke out, and revolutionary fermentation had already begun in the city. Then came the First Russian Revolution of 1905-1907. In addition, in these conditions, in St. Petersburg they started talking about the need for large-scale changes in the state agrarian policy.

Agrarian reform of Peter Stolypin

On July 9, 1906, Peter Stolypin headed the Government of the Russian Empire. One of the first initiatives of the new head of the Cabinet of Ministers was agrarian reform. The main decree was signed on November 9, 1906. The document was called: “On the Supplement of Certain Resolutions of the Current Law Relating to Peasant Land Tenure and Land Use.” The document talked about what Peter Stolypin said initially: “We must give freedom to the peasants, leave collective land ownership in the past and lay the groundwork for the emergence of a strong middle peasant class, which is already branded in the Soviet Union with the nickname “kulak”. In addition, the peasants were granted the right of free exit from the community, as was stated in the Decree that “every householder who owns land under communal law may at any time demand proprietorship of his property that belongs to more than two million householders. In total, a little more than 14% of all communal lands during this time passed into personal ownership, 1.6 million households appeared. An equally important part of the agrarian reform of Peter Stolypin was the resettlement of landless peasants from European provinces to Kazakhstan and Siberia. It was in the Asian part of Russia that they could acquire a land allotment. The tsarist authorities were actively campaigning among the denizens of the peasants of European and Central Russia, urging them to go to the development of new lands. Thus, only in 1907, for these purposes, 6.5 million copies of propaganda brochures and leaflets were issued. To make the peasants go even more willingly, the authorities promised them the best land, moreover, the move itself was free, and for this, they even provided special cars, popularly called "Stolypin". It should be noted that several decades later it was in these wagons, though already with bars and escorts, that thousands of people again went to Kazakhstan and Siberia, but not of their own free will. During the time of Stalinist repressions, hundreds of thousands of innocent people were sent to exile in these exact wagons. In addition, at the beginning of the century, immigrants traveled to these lands voluntarily, and agricultural equipment and even livestock were waiting for them there. Schools, baths, first-aid posts were built, that is, the authorities tried to create all conditions for new arrivals. In addition, the peasants came. In Kazakhstan alone, by 1917, more than 1.5 million people had resettled.

Stolypin Agrarian Reform and Kazakhstan

In regards to the Stolypin agrarian reform in Kazakhstan, it should be said that the authorities often did not take into account the interests and rights of the indigenous population. After all, the immigrants received land taken from the locals. Moreover, the most fertile allotments were seized, and Kazakhs living from time immemorial were relocated to unsuitable or hardly suitable lands for farming or cattle breeding. The tsarist authorities had pursued such a policy before. For example, if from 1893 to 1905 the Kazakhs lost four million acres of land, from 1906 to 1912 already more than seventeen million, then by 1917 45 million acres of land had been withdrawn from the use of the indigenous population. Mainly, such a policy was implemented in the most fertile regions of Northern Kazakhstan. In the same Kustanay district, 54% were withdrawn from all lands, and in Akmola and even more - 73%. This led to massive landlessness of the indigenous people and the growth of tension between the indigenous people and peasants-immigrants . From 1906 to 1913, over 430 thousand households settled in the Akmola, Turgai, Ural and Semipalatinsk regions. In the same 1913, “Temporary Rules on the leasing of state-owned land in Siberia, the Steppe Territory and Turkestan” was adopted, thus the authorities planned to create large resettlement farms here.

Обсуждение